by John C. Eastman

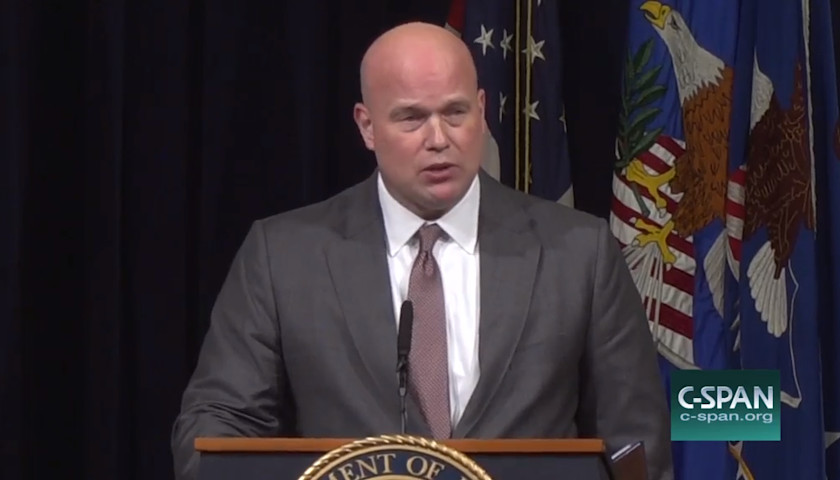

So let me get this straight. In his November 8 New York Times op-ed (“Trump’s Appointment of the Acting Attorney General Is Unconstitutional,” co-authored be George Conway), Neal Katyal writes that President Trump’s designation of Matthew Whitaker as acting attorney general is unconstitutional because the office of attorney general is a “principal office,” which can only be filled by someone who has been confirmed by the Senate. That would be the same Neal Katyal who served as acting solicitor general, also a Senate-confirmed position. And the same Neal Katyal whose boss, Attorney General Eric Holder, had served as acting attorney general at the end of the Clinton Administration and in the early days of the George W. Bush Administration. And the same Neal Katyal who served in an administration that closed out with another acting attorney general, Sally Yates, who acted like an embedded enemy within the Trump Administration until she was finally fired by the president for refusing to defend the president’s travel ban executive order—she claimed that there was no plausible defense for it, even though the policy was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court.

The double standard is so palpable as to be laughable.

To be fair, Katyal’s own position as acting solicitor general can be distinguished. The solicitor general’s office is arguably an inferior office, which means that the Constitution only requires Senate confirmation as the default position. Congress can, by law, vest the appointment of inferior officers in the president alone or in the head of the department. But that is not the case with either Eric Holder’s or Sally Yates’s appointments as acting attorney general. Either their appointments were also unconstitutional—and I don’t recall Conway or Katyal ever arguing that—or Whitaker’s temporary designation as acting attorney general until a successor can be named is equally valid. Conway and Katyal’s implicit attempts to distinguish those cases fall far short of persuasive.

“In times of crisis, interim appointments need to be made,” they admit. “Cabinet officials die, and wars and other tragic events occur,” but “it is very difficult to see how the current situation comports with those situations,” they claim. Sessions resigned following an election, but so did Holder’s and Yates’s predecessors, Janet Reno, and Loretta Lynch. Sessions was asked to resign, and it was a midterm election, but neither of those different factual circumstances would appear to be of constitutional significance.

Conway and Katyal also note that Holder and Yates were both serving as deputy attorney general (a Senate-confirmed position) at the time of their appointment as acting attorney general, and that the Senate confirmation to that post somehow transfers over to validate their appointments to a different, higher office. But if that is the case, then the same is also true of Whitaker, who had previously been Senate confirmed to the post of U.S. attorney. Conway and Katyal’s claim that “Mr. Whitaker has not undergone the process of Senate confirmation” to “scrutinize” whether he has the character and ability to evenhandedly enforce the law in a position of such grave responsibility” is therefore simply false. They presumably would argue that a U.S. attorney, though Senate confirmed, is not as significant a position as deputy attorney general, but then they would run headlong into the executive order issued by their former boss, President Obama, just days before he left office, designating the U.S. attorneys for the District of Columbia, the Northern District of Illinois, and the Central District of California as in the line of succession to serve as acting attorney general. And they would also run headlong into President Trump’s designation of Dana Boente as acting attorney general from her post as U.S. Attorney in Virginia, following his firing of Yates.

Their next line of argument undoubtedly would be that Whitaker’s immediately preceding position as chief of staff was not Senate confirmed, and that his prior senate confirmation in a previous administration was too remote to transfer over to the new appointment. But the Senate confirmations of both Holder and Yates as deputy attorney general, as well as Boente’s as U.S. Attorney, had all occurred in the prior administration, yet none of those appointments seem to have troubled Conway or Katyal. If the point of a prior Senate confirmation to a different office is, as Conway and Katyal contend, that the Senate has at least had a chance to scrutinize whether the person designated by the president as acting attorney general “has the character and ability to evenhandedly enforce the law,” then that function was fulfilled as much for Whitaker as it was for Holder, Yates, and Boente—to say nothing of Nicholas Katzenbach (1964), Ramsey Clark (1966), Robert Bork (1974), Richard Thornburg (1977), William Barr (1991), Stuart Gerson (1993), Paul Clement (2007), Peter Keisler (2007), and Mark Filip (2009), all of whom served as acting attorney general without Senate confirmation to holding that position.

Perhaps what we are seeing is the Trump effect on legal analysis, such as the argument made before the Fourth Circuit in the travel ban case in which Katyal himself was involved, that perfectly valid actions taken by other presidents are unconstitutional when taken by this president. But such a double standard is hardly conducive to the rule of law. If principal officers such as the attorney general can only serve, even in a temporary, acting capacity following a death or resignation, after Senate confirmation to the position, then we’re going to have headless departments of government quite often.

If, on the other hand, as recent history and tradition suggest, the president can temporarily assign someone to the duties of the office who has previously been Senate confirmed in another office, until a successor can be appointed with Senate confirmation, as Justice Scalia noted in NLRB v. Noel Canning has been the case since 1792, then that expedient practice should be as much available to this president as to any other.

– – –

John C. Eastman is the Henry Salvatori Professor and former dean at Chapman University’s Fowler School of Law, and a senior fellow at the Claremont Institute.